In this issue, three items by Charlie Alison, the first about the language we use for talking about the “other”; then a look at the stick maps of the Marshallese people, many of whom no longer have need of nautical cartography; and finally a short poem about two island birds. Even more finally, a note from the little white dog and a last word.

The Sticks and Stones

ESSAY

By Charlie Alison

When I was but a boy attending grade school on the northeastern edge of my town, I rode my bicycle a quarter mile east along the state highway to reach the school. From the opposite direction, from beyond the city limits, several friends — Kristi, Howard, Wanda, Clayton and Chris — rode the school bus into town from the hinterlands where they lived on farms.

My friends from the country talked differently than did I or my city friends. The talk of my country friends reminded me of the character Festus on the old TV show Gunsmoke. I would learn later that their way of speaking was a hill-country dialect, but at the time it was a captivating language to me full of color, candor and sly humor, especially so when contrasted with the typical attempts my city friends made toward humor during recess.

Before living in this town, my family had briefly lived on a Kansas farm. We took care of a black horse named Midnight stabled in the barn out back, and we inherited a large collie named Beauty as part of the rental agreement for the farmhouse. I was perhaps 3 or 4 years old and at the age of thinking I knew how to walk or maybe even run. My first self-initiated adventure in life amounted to a “sprint” across a pasture between our house and the neighbors, whom I wanted to visit. I slipped between the barbed wire and walked within the fenced pasture, and then I saw a bull approaching from a distance. I started running. The bull gave chase at a trot. I ran faster. I reached the far fence line with cheers rising from our neighbors, the MacGregors, or so I thought. They hadn’t been applauding my effort but were waving their hands wildly and shouting to distract the bull. It had worked.

Brilliant, as the British would say.

After moving to Fayetteville, Arkansas, that brief rural life made me feel a kindred spirit for my rural friends and some envy at their good fortune to live outside of the town proper. Not everyone in school felt the same way.

The first epithets I recall hearing in my young life were not profanity or obscenity, unless perhaps my father had hit his thumb with a hammer and sent a cursing word into the air that I’ve forgotten. No, the first I remember were words hurled by some of my town friends at these friends who rode the bus. The word “hick” was probably the first. “Hicks from the sticks.” Or “clodhoppers” or possibly “redneck,” although my recollection is that we didn’t hear the word “redneck” too much in grade school, that it came later and was only applied to rough-edged yahoos from Texas.

I didn’t exactly know the meaning of those words when I first heard them, but I understood the intent to taunt and tease and belittle. They were the first words that left me sad — for my farm friends in the moment, of course — but less sad for them than for the poor city boy who had spoken the words. How difficult must be his life to want to poke at someone else and laugh at them. With what sort of world was he contending?

I knew then I would have to make choices in life about whom to keep as a close friend and whom to let go. I thought they would be difficult choices, but they turned out not to be so.

Charlie Alison is a writer and editor. His non-fiction book, A Brief History of Fayetteville, Arkansas, is available through Arcadia Publishing.

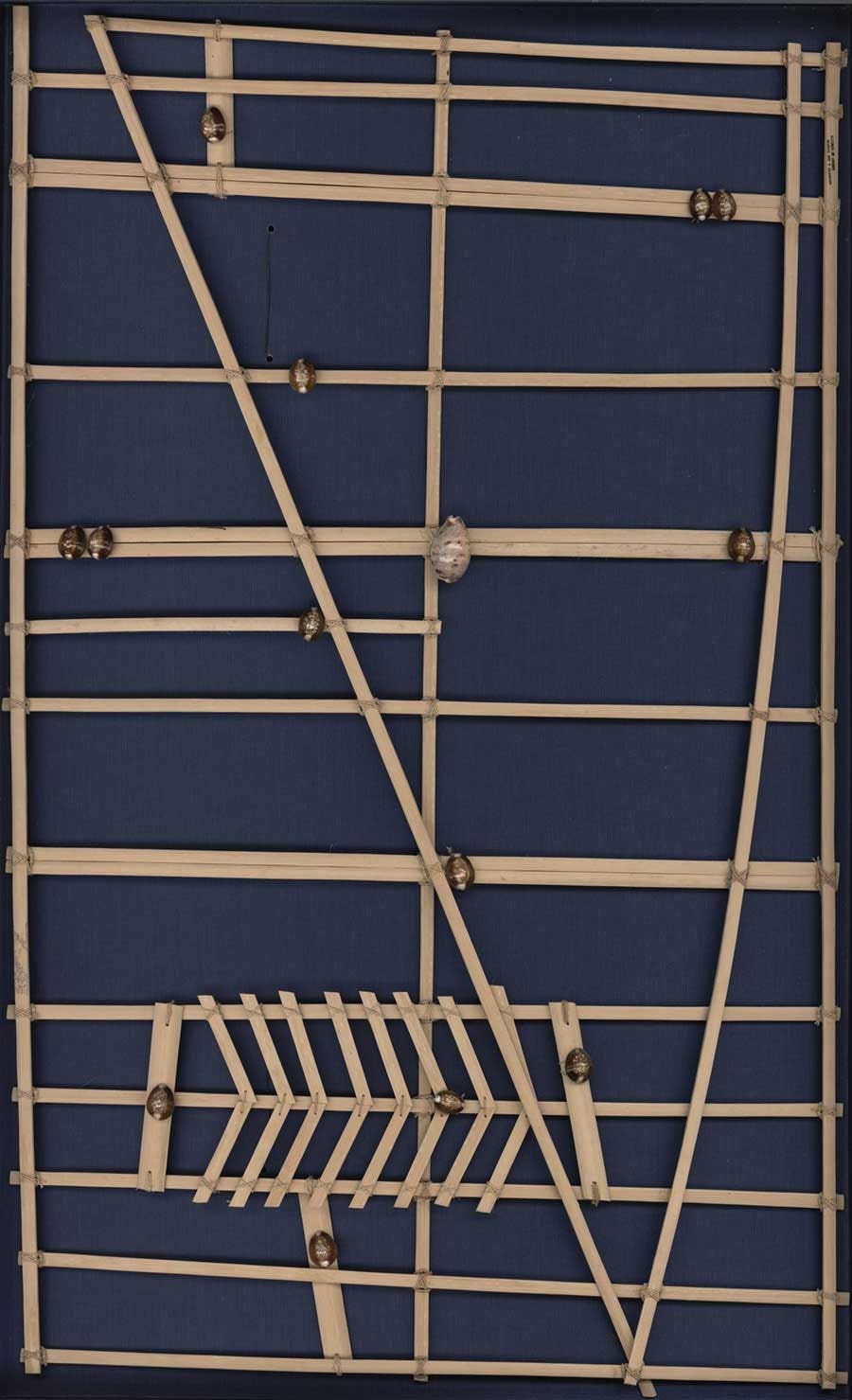

Marshallese Stick Map, circa 1920s

CARTOGRAPHY

The seafarers of the Marshallese Islands designed “stick maps” to guide their nautical travels between the many chains of islands making up the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

The maps are “three-dimensional,” taking into account both latitude and longitude but also the dimension of time — in this case the time that ocean currents and winds might affect the speed of out-rigger canoes upon the water. The physical distance between two locations on the stick map might be exaggerated or contracted to reflect that relativity of time.

The large shell at the center of the stick map above represents the atoll of Kwajalein. The herring-bone design near the bottom of the chart represents the influence of the northeast trade winds on the ocean swells after they pass through and around the Jaluit Atoll. The southern edge of the map, by the way, would be about 275 miles north of the equator.

Far to the northwest, the upper left corner, is a shell representing the Bikini Atoll. The United States forcibly removed its inhabitants in 1946 so that the atoll could be used for testing nuclear bombs — 23 bombs altogether over a 12-year period. A brief effort to resettle the atoll in the 1970s was abandoned after scientists reported dangerously high levels of strontium-90 and cæsium-137 found in the people who had returned.

Today, the various islands of the Marshallese are more heavily endangered by the effect of climate change on sea levels. A report issued in October 2021 by the government of the Republic of Marshall Islands and the World Bank showed four out of every ten buildings in the Marshall Islands capital of Majuro will be endangered by the rise of the sea. Flooding can be expected across 96 percent of the capital city. If current trends continue, the report said, the Marshallese government will face a series of increasingly costly adaptation choices to protect schools, hospitals and government buildings, not just at Majuro but across the archipelago. And there’s no guarantee that adaptations will win the day.

Ironically, today the largest population of Marshallese Islanders lives in the land-locked region of Northwest Arkansas, drawn there a generation ago by the availability of jobs in the poultry industry. Many of the Marshallese were adept at determining the sex of baby chicks quickly and accurately. The quick separation meant that the “broilers,” the industry term for male chickens destined for restaurant tables and grocery shelves, and the hens, which would live a longer life as egg producers, could be directed to their respective fates more economically than if they were raised together. The earlier the better, at least in the minds of chicken magnates, if not chickens themselves.

If a young Marshallese traveler were to make a stick map today, she would use it to reflect the greater travel times required by chicken trucks to crawl up and over the ridge tops of the Boston Mountains in search of chicken houses that are far off in the jillikens and the lesser times needed to descend steep, narrow roads into the next deep creek valley. And there might be small shells noting forgotten places like Edwards’ Junction, Japton, Snowball, Jupiter, Nail and the Southwest Experimental Fast Oxide Reactor.

Whipbirds Among the Islands

POETRY

By Charlie Alison

Along the Barrier Reef,

Among the islands near Cairns,

Two whipbirds sing their mating call.

The man bird gives a whistle that builds

With volume and verve until it cracks,

Then a woman bird snaps an end like a marble

Being dropped into a still, round pool of water.

Filling his chest, the man bird repeats the song,

And the woman bird’s snap at the end comes sharper

Each time until it sounds like the pop of a whip

Being snapped on the spine of a cow.

The man bird whistles again and again,

While the woman bird answers with her same sung song,

Strangers mating mellifluously for life,

Continuing their call and answer to the end.

What do they sing, one to the other?

A simple confirmation of proximity?

Where are you? I’m here.

Where are you? I’m here.

Or is the message less formal in tone,

A cheery lyric along another line?

Hey you. Who me?

Hey you. Who me?

Still another transliteration of the whistled tune

Might draw a more romantic turn.

I love you. I love you, too.

I love you. I love you, too.

Deciding the imagined conversations

Says less about a pair of whipbirds, of course,

Than it does about our own heartsong

And the coming of the end of day.

When a woman bird dies before her mate,

And no one is left to answer his call,

The man bird sings his song alone

And then answers for her upon his own.

Does he sing her part from custom or habit?

Does he sing to salve a heartless void?

Does mere loneliness drive his answering song?

Or does he hope no one will notice his loss?

Chronicles of the Little White Dog

By Mark Pennington

We took the little white dog over to Maddox's, where she engaged in status competitions with Maddox's much bigger and more rambunctious dog. At one point she got hold of some type of meat on a stick treat that belonged to the other dog. It was about 3 times longer than her head, and she was carrying that around, clearly thinking that there might be a chance to carry it out to the car.

We decided she needed to go out to do her business, which meant putting her in a harness, which meant removing the treat from her mouth. She clamped down with those jaws genetically designed for killing rats and other rodents in a fair fight and refused to let go. Thomas grabbed the stick part and literally lifted her off the ground by her bite so she was hanging like a fish being photographed on the dock.

Clearly the most entertaining she has ever been in her time with us.

The Last Word

Gloaming | 'glō-miŋ

While we were children, my brother, sister and I joined a host of neighborhood kids outside, staying as late into the gloaming of summer evenings as we could, turning over rocks in the creek to catch crawdads, playing hide and seek, and then chasing lightning bugs.

Our favorite game was called Murder at Midnight. It was 180-degrees the opposite of hide and seek. Instead of one person counting to ten and trying to find everyone who has hidden, one person goes off to hide while the others count and then strategize how to find the “killer.” The hider’s intention is to become so well hidden that he or she could slowly pick off searchers by tagging as many as possible before, during and after being found.

It was a game best played in the gloaming, when shadows crept deeply into the overgrown ivy, bushes and canopied tree limbs, veiling the hider more completely than even the full of darkness, which caused the eyes to adjust and the ears to become acute. Someone suddenly sprang from the shadow and you were “murdered.”

The gloaming, itself, is not so sinister. It finds its way to us through the Scots language and was very likely derived from the Old High German verb gluoen alongside similar uses such as the Middle English gloming, which itself derives from glōm, the Old English word for twilight.

But those two words, twilight and gloaming, have a difference, the former seemingly a more distinct point in time while the latter speaks to the slow fade of light toward the finality of night.

The author Joan Didion, who died this past winter, wrote:

The French called this time of day “l’heure bleue.” To the English it was “the gloaming.” The very word “gloaming” reverberates, echoes — the gloaming, the glimmer, the glitter, the glisten, the glamour — carrying in its consonants the images of houses shuttering, gardens darkening, grass-lined rivers slipping through the shadows. During the blue nights you think the end of the day will never come. As the blue nights draw to a close (and they will, and they do) you experience an actual chill, an apprehension of illness, at the moment you first notice; the blue light is going, the days are already shortening, the summer is gone... Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning.1

The Dutch word gloeien took a similar path from the Germanic but, like twilight, is used more singularly for “glowing” while the Dutch word for the last ebbing light of day is schemering. And, though it now lingers in your mind, it is the last word. CEYA

Have an interesting word? Send it to editor.ozarkhollow@gmail.com. Include your name and hometown as well as why the word is of interest to you and what, if anything, you know about the word.

Other Contributors to this Issue

Foreign Correspondent — Polly Glott

Editor of the Overstated — Max Tout

Understudy to Graphic Designer — Justin Kase

Didion, Joan. Blue Nights (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011).