In this issue, Michelle Parks writes about one fine spring evening when country met city. Matt McGowan tells a tale — half real and half imagined as real — from his hometown. And, of course, a wag of the little white dog and a last word.

Concert Counterpoint

By Michelle Parks

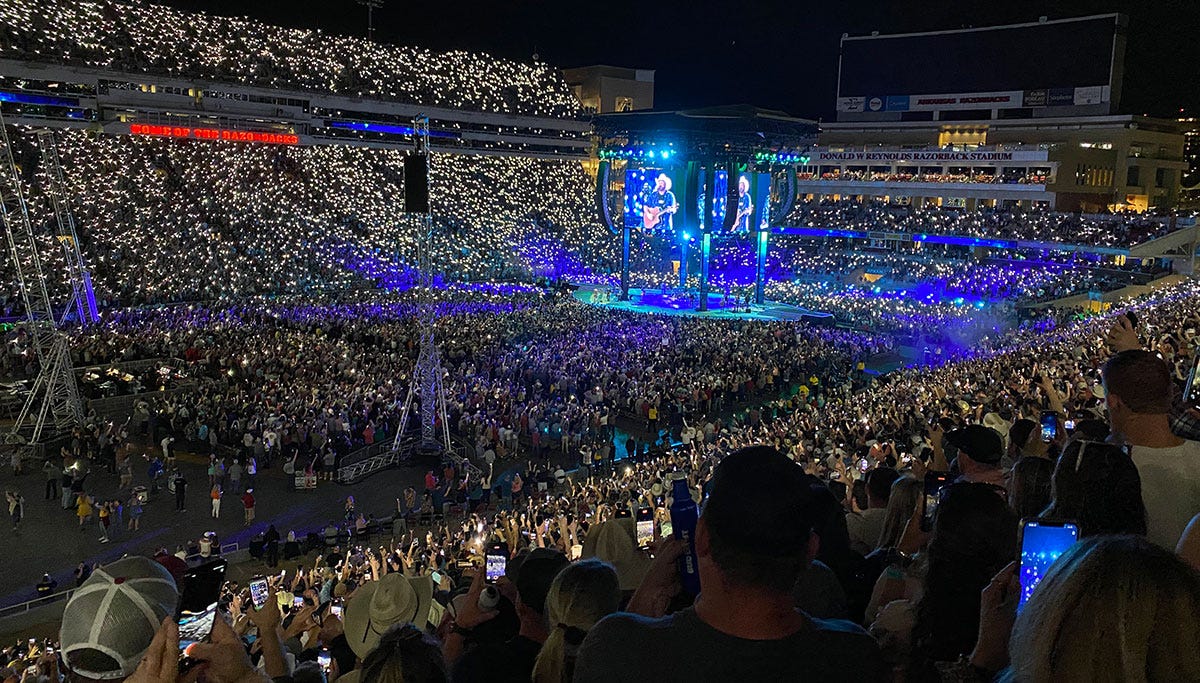

On a Saturday night in April, a momentous event happened in Fayetteville. Garth Brooks, the country music superstar, came to town and put on a concert in Razorback Stadium on the University of Arkansas campus. Concerts in this athletics landmark are rare.

Excitement built all day. People from across the region and neighboring states pulled cowboy boots and hats from their closets in preparation. Some 80,000 souls stuffed a stadium built for 76,000, with seats and chairs filling the field from goal line to goal line.

For years, the old basketball stadium, Barnhill Arena, had served as the university campus venue for concerts by touring artists of all musical styles. So, this show on the football field was a thrilling occurrence.

Traffic had been heavy all day. Police units positioned around town watched for speeders and generally helped to corral the chaos.

Instead of attending the concert, I’d gone to an art show opening. The works of 20 local artists were harmoniously arranged in a cozy gallery space along Archibald Yell Boulevard.

Some of us stepped outside to listen to a four-piece acoustic bluegrass band as they played on an improvised stage.

The wind picked up, and clouds started to form. A storm was coming.

By the time I left the art opening, the concert had started. I hoped to find some takeout dinner so I wouldn’t have to cook.

I dialed the number for a south Fayetteville Thai restaurant, but the line was busy. Stalled taillights of trucks and cars jammed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard near the stadium. Finding food on that route was out of the question.

So I headed north, up College Avenue away from the chaos. Above the lonely streets, the sky darkened with rain clouds.

As the road dipped near the old Doc Murdock’s, once home to countless weekends of two-stepping and line dancing, a Fayetteville police SUV ran its lights and cut into northbound traffic. He pulled up to face me in the right lane.

Then I saw why.

A deer lay flat, belly to the ground, its back legs splayed on the sidewalk. It struggled to pull itself forward with its front legs onto the bordering grass. A car must have hit it. Eyes wide, it looked around, confused and desperate.

The policeman got out of his SUV and stood on the sidewalk, watching over the deer. He radioed someone. All he could do was wait for help to arrive.

Cars carefully detoured around this temporary obstacle. Dark clouds continued to gather. Elsewhere, music played. Hours later, deep in the night, lightning flashed and thunder rolled.

Michelle Parks is a writer and editor in Washington County, Arkansas.

Run Like the Deer

ESSAY

By Matt McGowan

Webb City, Missouri, a town of about 6,500 people when I was growing up there in the 1970s and 1980s, had more than its share of eccentric people. I say this because that was and still is my impression, but it might not be true. As a percentage of the overall population, Webb City could have had fewer eccentric people than New York City, for example, or certainly New Orleans, where they seem to crawl out of the woodwork.

Still, it was my impression, and these days that seems to be enough to be considered the truth. In my defense, several people I know share that impression, although I can’t vouch for their credibility.

To add to the unscientific mushiness of my perception, I always assumed it had something to do with the water or — more specifically as it relates to the water — the mines. Have you ever been to Butte, Montana? If you have, you know what I mean. There’s something special, and perhaps tragic, about living among the ruins, remnants and ghosts of an old mining town. First there was no one, then overnight there were thousands, tens of thousands. Webb City was a boom town, a place where fortunes were made, the land was destroyed, and liquor was served by the barrel. And then one day it was gone. Everyone disappeared. They picked up their tools and hustled down to Pitcher or Commerce. Well, nearly everyone.

We had colorful characters: Page Boy, the Missouri Runner, the person who drove a car without tires, and the poor soul who I will call the smock-wearing/kitchen-knife-wielding/silent-screaming woman, but all of them combined could not compete with Billy Pearson. I saw him myself, many times, with my own eyes, when other people were there — in other words, there were witnesses — and yet I’m still not sure he existed. Such was the lore and legend and mythology surrounding this larger-than-life character.

We heard stories about him as soon as we could walk. When we were quite young, not yet out of elementary school, there were three popular and dramatic ones circulating, and I suppose these tales, for me anyway, solidified him as a caricature or legend or — sadly — a monster, years before I even saw him. The stories probably were not true — two were seemingly impossible and one was pathetic and scary — and likely were manufactured by a bored prankster or malevolent psychopath.

The first one was simple enough, and really not even a story. People said Billy could “run like a deer.” I don’t remember where I first heard this or who told us, but I do remember that whoever said it also mentioned that Billy could hurdle fences without breaking stride. Now, if you ever saw Billy, you knew all of this was garbage. He had an odd-shaped body — short legs and longer torso punctuated by a wildly prodigious beer belly — and interesting way of moving — sort of scooting along by shuffling his legs, his arms swinging loosely at his sides — but to say that he could run like a deer was just pure nonsense.

The second story was hilarious, if you think about it. Someone told us the authorities rounded him up — maybe as a result of the next story, if true — and took Billy to the state mental hospital in Nevada, 60 miles north of Webb City. As the story goes, the officers who delivered Billy to the hospital made sure he was taken inside and checked in and all that, confident that he was secure there and might get some help. But when the officers returned to Webb City, an hour or so later, Billy was already there. Somehow he’d beaten them back to town, in an absurdly short period of time, presumably by running like a deer and hurdling several fences.

Other stories seemed too cruel to be true. Maybe they started with a small bit of truth but grew into horrible fables in the retelling.

I don’t remember the first time I saw him, but soon after that, for a while anyway, he was ubiquitous. Every time you turned a corner, there he was, walking down the street, or, more likely, standing on a sidewalk and writing down words on a street sign. This scribing was his purpose and cause for a while and could be intense; I have a vague memory of him getting angry about it, shouting — mostly to himself — and waving his fist. This scared people and, no doubt, added to the lore.

Even more so because his eyes were so intense, and his body moved jerkily when he talked to you. As my brother and I’m sure others know, Billy could be rude and confrontational. Apparently, he could also be lewd, although I never observed this. My father-in-law, who was a bit of an eccentric himself and had a long history with Billy, insisted that Billy stood in front of the house so he could engage with my girlfriend (and future wife) and her sister. More than once my father-in-law had to come out of the house and “encourage” Billy to get going.

“You had to be tough to grow up on the West End,” my father-in-law used to say, and that’s where Billy and his mother lived, in a small house a block or two west of the high school. When we reached that age, a bunch of us played touch football on the expansive front lawn. One day, Billy came rumbling across the street and inserted himself into the middle of our game. (Did the ground shake like an earthquake? This can’t be right.) He was not running like a deer, nor were there any fences to hurdle, but, despite his impressive girth, his shoulders were back, and his spine was straight, and he was scurrying along with surprising coordination and agility.

He made a beeline for Mike Kahwaji. The way Billy came at Mike indicated Billy had spotted him from far away and needed to get a closer look. The rest of us were invisible. Mike did look different. His family had moved to Webb City from Southern California, but his ancestors were Lebanese. His skin was a little darker, and his hair was jet black and shiny.

“Look at that!” said Billy, reaching for Mike’s hair. I can’t remember if he actually touched it. And then, ironically, Billy said, “With hair like that, you should go to Hollywood.”

Mike, the most intelligent among us, and probably the least gullible or most skeptical about the fallacies of legend and mythology, just stared at Billy with a look that said, “You’re Billy Pearson.”

Yes, he was.

Chronicles of the Little White Dog

Editor’s note: The guitarist Leo Kottke wrote an instrumental song titled “Room 8,” included on his Mudlark album in 1971. The title came from the name of a cat that wandered into a classroom at the Elysian Heights Elementary School in Echo Park, California, back in 1952. It stayed at the school through the course of the school year and then disappeared during the summer, returning each fall with the start of school. This went on for many years, and Room 8 died in 1968. The students of the school raised money to bury Room 8 in the Los Angeles Pet Cemetery.

By Mark Pennington

This is definitely how the little white dog imagines her passing. Maybe a bigger stone. Maybe a statue.

The Last Word

gowrow | 'gau̇-rau̇

Writing for the Arkansas Historical Quarterly in 1950, Vance Randolph described a menagerie of fantabulous animals endemic to the Ozarks. Randolph had picked up descriptions of these wild beasts — or “aprocryphal animals,” as he put it — while he toured the region in search of folklore and folksayings during the early and mid-20th century.

Among them were the jimplicute, a ghostly monster that grabs humans by the throat and sucks their blood; the kingdoodle, a large reptile “longer’n a well-rope, an’ fourteen hands high”; the willipus-wallipus, which was also the name of a large road-building steam-driven machine; the snawfus, an albino deer that can leep into the treetops; and the gally-wampus, an amphibious panther-like mammal that swims like an enormous mink.

But the best known and longest-lived legend of them all was the green gowrow, the existence of which was first reported in the Arkansas Gazette issue of Jan. 31, 1897.

Elbert Smithee wrote a report of a gowrow and its death, based on the story told him by William Miller, a Little Rock businessman who had traveled to northern Arkansas:

Immediately upon my arrival at Blanco I instituted inquiries and I was amazed to find that the people of the whole township, and of St. Joe and Richland townships, were in a fever of excitement over what they called the “gowrow,” which they described as a terrible animal which slaughtered cattle, horses, hogs, dogs and cats. The gowrow had terrorized the community for several months but though tremendous attempts had been made to capture it, all of them had proved unsuccessful. The animal would steal down from the mountains at night and commence its depredations. He would break into cowsheds and kill and devour the cows and calves. Several times he had been interrupted in his blood-thirsty work, but he always managed to escape, carrying one of his victims with him.

Even into the 1920s, there were Ozark residents who insisted that gowrows might still roam the woodlands of north Arkansas and southern Missouri, though Randolph said he did not pretend to know whether they were speaking in earnest. If the imaginary gowrow beast was ferociously complex in physical structure, the etymology of the word gowrow turned out to be rather simple. It is the sound one of these ghastly creatures makes during its foraging, something like nom-nom-nom today. And that’s the last word. CEYA